Ed note: This review first published on Jazz Police.com in June 2013.

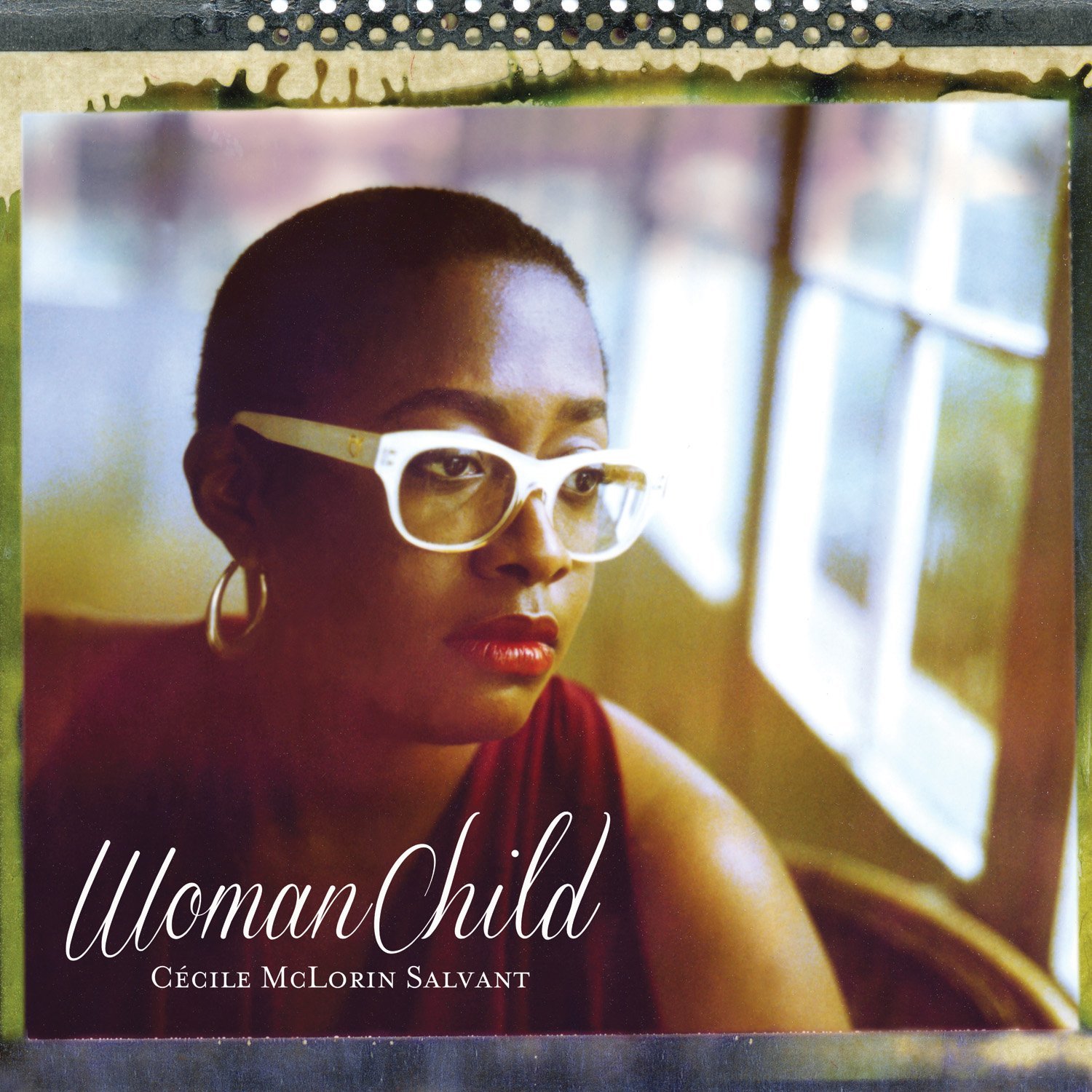

“If music came with a ‘100% natural and organic” sticker, this CD would have it on the cover. This is music of the human heart. Undiluted. Timeless.” Ted Gioia (liner note, Woman Child)

In the 2010 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Vocalists Competition, a young woman barely into her 20s seemingly came out of nowhere to take top honors. And now that same young singer, at 23, has released a remarkable recording for Mack Avenue Records, aptly titled Woman Child.

Who is Cecile McLorin Salvant? Born and raised in Miami of French and Haitian parents, Salvant started classical piano at age 5, sang in the Miami Choral Society at age 8, and went to France to study law and classical voice (at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory in Aix-en-Provence). There she became immersed in improvisation (instrumental and vocal), working with clarinetist Jean-François Bonnel. She made her first recording, Cecile, with Bonnel’s Paris quintet, and a year later, won the Monk Competition. The contract with Mack Avenue and a January 2013 appearance on Piano Jazz: Rising Stars followed, as well as the opportunity to lend her voice to Chanel’s “Chance” ad campaign. McLorin Salvant’s star has been on a fast rise, but perhaps none of her achievements sufficiently predicted the startling maturity of Woman Child.

Salvant’s choice of material reflects her interest in the less familiar, seldom recorded repertoire of jazz and blues, from early 20th century through the full history of the music, as well as her own talents as composer, lyricist and (on one track) pianist. Her apparent sources of inspiration cover the legends from Bessie Smith to Billie Holiday, from Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughn to Nina Simone, Abbey Lincoln and Betty Carter. Especially for a young singer, such muses can also inspire imitation. Noted Cecile in a recent interview for Downbeat, “ Following all the great vocalists in this music, how do you make it your own?…You have to remember yourself in the music—express your thing.” Already, McLorin Salvant seems to have no trouble expressing her thing. There is no note of imitation – this is an artist who has an uncanny ability to meld classical training, improvisational talent, and dramatic flair into a wide-ranging and unique voice. Her cohorts on Woman Child were well chosen to support her journey, including another young virtuoso, pianist Aaron Diehl, along with veterans, bassist Rodney Whitaker, guitarist/banjoist James Chirillo, and drummer Herlin Riley.

Woman Child starts chronologically at the beginning, with J. Russel Robinson’s “St. Louis Blues,” recorded 90 years ago by Bessie Smith. Notes McLorin Salvant, “Bessie became a fundamental part of how I approached singing this music, her balance of vulnerable and strong.” It’s a balance Cecile finds throughout the album. Other than the clarity of the recording, you might think you are listening to Bessie herself as Cecile, accompanied only by James Chirillo’s guitar, sings with a lilting, sultry, nuanced flirtiness, perfectly holding notes that add to the coquettish delivery. An even earlier choice, “Nobody” (Bert Williams and Alex Rogers) comes from the early 1900s musical, Abyssinia. Cecile finds both the humor and honesty of the lyric, her shifting moods mirrored by Diehl’s alternately prancing and balladic accompaniment; and Riley’s two snare hits add a comic touch to the finish.

Bessie Smith most famously covered Clarence Wiliams’ “Baby Have Pity on Me” in 1930 – at least most famously until McLorin Salvant picked it up for Woman Child. With Chirillo’s supportive counterpoint and some abstract interjections from Aaron Diehl, she lands somewhere between Bessie and Billie, delivering a classic, seductive blues with a strong current of hope. Jumping a generation, McLorin Salvant seamlessly follows an original, elegant instrumental “Prelude” composed by Diehl with “There’s a Lull in My Life” (Gordon and Revel), from the playlists of Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole. There’s a 30s-40s sound (“the clock stops ticking… the world stops turning…”) as Cecile make her pain beautiful, timeless, almost seductive, with hints of Billie, Ella, and particularly Sarah Vaughan.

One of two songbook standards, Rogers and Hart’s “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” also suggests Sarah to some degree. Diehl’s staccato piano chords and Riley’s caressing brushes accompany the singer’s first verse, yet only the voice carries the melody as Cecile pulls the listener in close to hear the story. A bass-fed interlude leads into Whitaker’s swinging solo, repeating the storyline without words; Diehl’s solo is filled with exquisite lines. Sticking with the lyric (no scatting!), McLorin Salvant nevertheless fills her last verse with horn-like phrases; like a taffy pull she tugs salty and sweet from those words, placing accents where you might least expect them. And her vocalese energizes Harry Woods’ “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” stretched over 8+ minutes. Her use of phrasing, timing, and tempo is so elastic that, while the band offers incomparable support, you also sense that the instrumentation was totally unnecessary—McLorin Salvant creates the sounds of an ensemble by herself, and seductively so. Diehl does strut his stuff on the instrumental interlude, with runs at breakneck speed in his right hand and slower comping from left, using multiple voices just like McLorin Salvant. Whitaker also solos in rapid fire fashion, while Cecile then keeps the listener off balance by slowing it down only to speed up again, and slow it down again before the brisk finale. Her unforgettable last line pierces the stratosphere at the top of her (or anyone’s?) range.

Two tracks in particular address the African American experience as reinterpretations of the past from a more contemporary perspective, not to defy or correct but to re-examine and revisit. The arrangement of the traditional “John Henry” brings a Latin slant to the rhythm, Cecile’s voice nearly a capella, with no melody at all coming from her heavily percussive (hammering!) band. But it’s the inclusion of Sam Caslow’s “You Bring Out the Savage in Me” that serves as the album’s vortex. Taking the song from the 1935 repertoire of singer/trumpeter Valadia Snow, McLorin Salvant turns the “jungle music” stereotype inside out. Without scatting a note, she becomes a snaky horn, manipulating her voice via dynamics, note choices and phrasing, stabbing at the social norms of the 30s with such power and energy that the song, in the hands of this seductive sorceress, works in 2013. “I think you can make fun of the idea of jazz as “savage music” even while wanting to be primal,” says Cecile in the album’s liner note.

The remaining tracks highlight McLorin Salvant’s talents as composer and pianist. On “Le Front Cachet Sur Tes Genoux” (literally, “the front seal on your knees”), Cecile wrote music for the text of a poem by Haitian Ida Faubert (“Rondel”), which as I can best translate is a sad love poem. At home in her native language, McLorin Salvant creates a beautiful waltzing ballad regardless of meaning. With crystal clear articulation, those comfortable with the language will easily translate. Diehl and Whitaker provide elegant solos in support. The brief closing track, the original “Deep Dark Blue” is a tragic, not sweet ballad, with a sharp edge that cuts through any suggestion of wistful longing. Cecile’s title tune opens and closes with Whitaker’s bass comments, an Abbey-Lincoln-esque anthem to women’s independence that fully displays McLorin Salvant’s musical and emotional range, as well as Diehl’s stylistic arc, from light swing to multi-layered symphonics.

Perhaps most surprising of all is Cecile’s tour de force on “Jitterbug Waltz.” Accompanying herself (solo) on piano, she launches a three-note vamp throughout the song and alternates her higher and lower voices as if carrying on a two-way conversation. Like the many roots of her vocal music, McLorin Salvant’s piano seems part Waller in its swinging energy, part Monk in its wide voicings and rhythmic somersaults, and every bit as intriguing as her voice—sweet, sassy, intelligent and bold.

Few modern vocalists manage to so successfully recall the past while keeping eye and ear in the present, and to do so with such precision in intonation, articulation and overall musicianship. That Cecile McLorin Salvant is at this pinnacle at age 23 is a bit scary. Fortunately, she seems fearless.